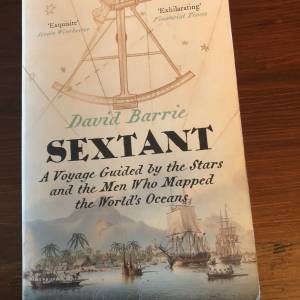

Le Sextant.

J'ai récemment eu le plaisir de lire la fabuleuse histoire d'exploration maritime de David Barrie, intitulée « Sextant », alors que nous naviguions vers et depuis et autour des Baléares. L'histoire d'hommes comme Cook, Fitzroy, Anson, Flinders et Vancouver est intimement liée à l'histoire du développement de la navigation céleste. L'auteur raconte l'histoire alors qu'il était lui-même engagé dans une livraison transatlantique d'ouest en est d'un voilier de 35 pieds. C'est une série captivante de fils qui gardera le lecteur engagé pendant des heures.

Quelle chance nous avons aujourd'hui. Le GPS peut nous donner notre position en temps réel sur un affichage de carte en mouvement. Cela rend la navigation plus sûre mais encourage malheureusement aussi la paresse. À quelle fréquence transcrivons-nous la lecture de la position GPS sur le journal de bord du yacht ? Je recommanderais que ce soit une corvée horaire. En cas de panne du GPS ou du système électrique du yacht (plus probable), on aurait au moins une dernière position connue comme point de départ fiable pour une navigation « à l'estime ». La navigation à l'estime n'est cependant pas viable si elle n'est pas complétée par d'autres formes de navigation plus traditionnelles, à savoir le relèvement des caractéristiques côtières ou les balises radio. Cela peut suffire sur les côtes mais au large et hors de vue, que faire ?

"Sextant" m'a donné un indice et aussi une chance d'imiter Barrie et de prendre quelques vues du soleil. Résoudre votre latitude de midi locale par passe méridien est facile. Nous nous sommes entraînés et avons réussi à résoudre notre latitude à moins de 5 'ou arc ou 5 nM. Nous avons pensé que ce n'était pas mal pour les navigateurs amateurs avec une expérience limitée. La navigation céleste est amusante et la gratification est instantanée car les positions calculées peuvent être comparées à la lecture de la position GPS du yacht. Cela pourrait inciter l'équipage à s'entraîner, le membre d'équipage le moins précis achetant une tournée de bières à terre !

Nous avons également essayé un correctif de midi par passe méridien. C'est un moyen rapide et simple (mais suffisamment précis) de calculer la latitude et la longitude simultanément lorsque le soleil atteint son zénith à votre position locale de midi. Cela oblige le navigateur à mesurer le point culminant du soleil dans le ciel tout en notant l'heure à laquelle cela se produit. Il est préférable de prendre une série de vues avant midi en notant leurs heures, puis de régler le sextant sur ces angles lorsque le soleil commence à descendre et de noter ces heures. Cela vous permettra d'éliminer les « points de données extérieurs » et de faire la moyenne des temps pour déterminer aussi précisément que possible l'angle et l'heure du passage du méridien. Nous avons réussi à résoudre notre position dans la mer d'Alboran à 17,5 nM près. Pas très précis vous pourriez penser et certainement pas une position sur laquelle se fier lorsqu'il y a une chance de toucher terre dans l'obscurité. Cependant, être capable de trouver votre position n'importe où sur la Terre à moins de 20 nM sans aide numérique extérieure est très utile.

J'ai résolu de sortir le sextant de sa boîte à chaque croisière. La pratique rend parfait et des précisions beaucoup plus élevées sont possibles. Si vous voulez comprendre les principes simples de la navigation céleste et ensuite apprendre à les appliquer dans la pratique, il n'y a pas de meilleur livre à préparer que le désormais classique « Navigation céleste pour les plaisanciers » de Mary Blewitt.